- Kyiv School of Economics

- People

- Stories

- #KSEVoice A new look at the relationship between human capital and social cohesion in a country

The importance of strong national social cohesion for a country’s socio-economic development is hard to exaggerate. Strong social cohesion is associated with increase in economic development, increase in abilities to deal with economic downfalls, increase in social health and many other positive outcomes. This article suggests a way of strengthening national social cohesion through strengthening of the national human capital. According to the article, the most effective way of doing this is via strengthening of the national identity awareness factor of national human capital. The research questions of the analysis are as follows:

Research Question 1: Is the level of education in a country associated with the level of NSC in that

country?

Research Question 2: Is the level of national identity awareness among people in a country associated with the level of NSC in that country?

Research Question 3: Is using the measures of education and national identity awareness in a country’s population a better predictor of the level of NSC than either measure alone?

The method the article utilized is the method of regression analysis. The source of the data utilized in the analysis is Human Development Reports published by the United Nations. Data for six consecutive years (2000-2005) was utilized.

Key words: human capital, cohension, welbeing, economic development, policies.

Introduction

The issue of social cohesion within a country has been growing in its importance globally. Finding a solution to weakening social cohesion is becoming more urgent and “many developed countries are worried about how they can maintain cohesion in societies that are home to ever-more disconnected communities” (Keeley, 2007, p. 15). Social cohesion is marked by the bonds that bring people together in a society. It is the myriads of links among diverse groups in a society, when there are no clear barriers and no alienation among the groups, and people feel like a unified nation. Social cohesion is also transparability between social groups in a society, which allows for opportunities for socio-economic mobility. Social cohesion can be an effective tool in national development, as it can mobilize a population to accomplish greater goals and to get more things done (OECD, 2001). Societies with s high degree of social cohesion more effectively realize collective goals of national development (Jenson, 1998), while those with a high degree of social polarization experience impairment of the economy’s ability to deal with economic shocks (Rodrik, 1998). High levels of social cohesion in a society are generally associated with higher quality of institutions, a factor that is known to be strongly positively correlated with successful socio-economic development (Alesina, Devleeschanwer, Easterly, Kurlat, & Wacziang, 2003; Bossert, D’Ambrosio, & LaFerrara, 2006; Easterly & Levine, 1997). As Easterly, Ritzen, and Woolcock (2006) put it, A country’s social cohesion is essential for generating the confidence and patience needed to implement reforms… On the other hand, countries strongly divided along class and ethnic lines will place severe constraints on the attempts of even the boldest, civic-minded, and wellinformed politician (or interest group) seeking to bring about policy reform. We argue that the strength of institutions itself may be, in part, determined by social cohesion. If this is so, we propose that key development outcomes… should be more likely associated with countries governed by effective public institutions, and that those institutions, in turn, should be more likely found in socially cohesive societies. (p. 103-104) According to Easterly et al. (2006), socially cohesive societies have always grown faster than less cohesive societies and are more likely to generate governments that have an “all-encompassing interest” (p. 109) in promoting growth. According to Kawachi and Kennedy (1997), “that social cohesion enhances wellbeing is by now a well established fact” (p. 1038). Putnam (1993) suggested that a breakdown of social cohesion threatens the functioning of democracy. Social cohesion, according to Keeley (2007), is truly the foundation of national stability. As societies become more diverse, with governments that are often not able to unite them, social cohesion, this glue that unites a nation deteriorates (Jeannotte, 2003; Keeley, 2007; Phipps, 2003). For example, Jeannotte (2003) stated that, for the period of 1996-2002, the proportion of people in Canada who felt excluded with no place in society increased by 15%. It is important to find ways to build cohesion in societies. This paper applies human capital (HC) theory to the issue of national social cohesion (NSC) and suggests ways to improve the state of this important factor.

Definitions

Social cohesion has many definitions. According to Helliwell (2001) and Jenson (1998), social cohesion is identified by shared values and commitment to a community. Easterly, Ritzen, and Woolcock (2006) defined social cohesion as “the nature and extent of social and economic divisions within society” (p. 105). They further added: As such, socially cohesive societies… are not necessarily demographically homogenous, but rather ones that have fewer potential and/or actual leverage points for individuals, groups, or events to expose and exacerbate social fault lines, and ones that find ways to harness the potential residing in their societal diversity. (p. 105) Based on the Council of Europe definition, social cohesion is “society’s ability to secure the long-term well-being of all its members, including equitable access to available resources, respect for human dignity with due regard for diversity, personal and collective autonomy and responsible participation” (Council of Europe, 2005, p. 23). In addition, “Social cohesion… takes account of how the various social players interact and the degree to which they succeed in ensuring the wellbeing of everyone” (Council of Europe, 2005, p. 15). The Canadian Senate defined social cohesion as the capacity of citizens to live together in harmony with a sense of mutual commitment (Dragojevié, 2001). Social cohesion “links together individual freedom and social justice, economic efficiency and the fair share of resources, and pluralism and common rules for resolving all conflicts by peaceful means” (Council of Europe, 2005, p. 15). The idea of freedom implies “equality in the provision of equal access to the material goods, and social and cultural amenities” (Council of Europe, 2005, p. 16). Social cohesion is based on community bonds, the sharing of values, a sense of belonging and the ability to work together” (Council of Europe, 2005, p. 24). Social cohesion is a state of affairs in which a group of people demonstrates an aptitude for collaboration that produces opportunities for change (Ritzen, Easterly, Woolcock, 2000). According to Ritzen (2001), social cohesion ensures open access to benefits and protection for all members of society. Other prominent definitions of social cohesion are “the extent to which people respond collectively to achieve their valued outcomes and to deal with the economic, social, political or environmental stresses that affect them” (Reimer, Wilkinson, & Woodrow, 2002), “a state of affairs concerning both the vertical and horizontal interactions among members of society as characterized by a set of attitudes and norms that includes trust, a sense of belonging and a willingness to participate and help, as well as their behavioral manifestations” (Chan, Chan, Benny, 2003, quoted in Jeannotte, 2003, p.7). Jenson (1998) identified five important dimensions of social cohesion: belonging, inclusion, participation, recognition and legitimacy. These dimensions are echoed by the Report on social cohesion published in the UK in 2006 (Turok, Kearns, Fitch, Flint, McKenzie, Abbotts, 2006). According to the Report, social cohesion is a broad term which includes five major dimensions: material conditions (employment, basic income, health, education, housing), passive relationships (tolerance, order, peace, low crime), active relationships (positive social interactions), inclusion (social integration), and equality. Jenson’s (1998) five dimensions of social cohesion include: belonging, inclusion, participation, recognition, legitimacy.

Relationship between National HC and National Social Cohesion

A number of researchers view the weakening of social cohesion as a source in widening the gap between the wealthy and the rest of the population (Kawachi & Kennedy, 1997; Moller, 2000; OECD, 2001). For example, Moller (2000) suggested that “a growing dichotomy between the elite and the rest of the population puts a question mark on social cohesion inside many societies-a cohesion that has been and still is the foundation for stability” (Moller, 2000, p. 114). Kawachi and Kennedy (1997) stated that “one notion that has existed for some time is that widening of the gap between the rich and poor might result in damage to the social fabric” (p. 1038). According to OECD (2001), an increasing divide between the highly-skilled and the unskilled is a significant cause of social cohesion’s deterioration. To determine how this divide is formed and what the mechanism is through which this divide leads to social cohesion deterioration, it is helpful to explore who comoprise the elite social class. They are the movers and shakers in the country, those who make economic and socio-cultural decisions. They differ from others because of the resources, power, and positions they posses, as well as their unique abilities, skills, talents, and vision. The first three factors may have little to do with actual individual effort and qualities, as they may be inherited or acquired by illegal means. The last four variables comprise human capital, which is a combination of an individual’s or group’s knowledge, skills, abilities, attitudes, and experiences that are relevant to economic activity and help individuals and groups be economically productive (Becker, 1964; Heckman, 2000; Jaw, Yu PingWang, & Chen, 2006; Mincer, 1958; Schultz, 1961, 1971; Smith, 1776/1937). The term economic encompasses all activities that directly or indirectly create wealth or income (OECD, 2001). Unique abilities, skills, talents, and vision put individuals who possess them ahead of everyone else. Representatives of the poor social class typically do not possess the qualities that are highly economically productive. The productivity of their HC is low. Therefore, it is possible that an increase in the differences in the level and quality of HC is an important factor that leads to deterioration in social cohesion. Consequently, we suggest that the mechanism by which the divide the wealthy and the poor takes place through utilization of different levels and quality of HC. The connection between social cohesion and HC has already been established. According to the 2001 OECD Report, “for growth and prosperity to be sustainable, social cohesion is required; here, the role of human capital is vital” (p. 17). Investment in human capital “is at the heart of strategies in OECD countries to promote economic prosperity, employment, and social cohesion” (OECD, 1998, p.7). According to Kawachi and Kennedy (1997) and Kaplan, Pamuk, Lynch, Cohen, and Balfour (1996), the lack of investment in human capital is a major pathway that negatively affects social cohesion. According to classical HC theory, HC is a flexible factor and can be developed by investment of appropriate resources. As Schutlz (1981) put it, HC includes “attributes of acquired population quality, which are valuable and can be augmented by appropriate investments” (p. 21). Consequently, positively augmenting the level of HC of underprivileged groups in a country by investing in their HC may lead to strengthening social cohesion. According to OECD (1998), “high and persistent unemployment and low pay affecting significant sections of the working-age population risk becoming threats to the social fabric unless they are addressed effectively and in good time” (p. 8). Many authors above viewed HC mainly in terms of education. Thus, the major application of HC theory to social cohesion may be raising the education level of the poorer portion of the population. This suggests that increasing the level of national HC (NHC) and, consequently, the level of social cohesion in a country (national social cohesion, NSC), may be achieved via increasing the level of education that low socio-economic people have. However, increasing the level of education is not necessarily associated with an increase in social cohesion. For example, according to OECD (2011) statistics, tertiary education entry rates in OECD countries increased by 25% during the preceding 15 years; however, these same countries reported a declining state of social cohesion (Keeley, 2007). This may suggest that raising the level of education is not enough, and additional actions are needed along with improvement in education rates. The contribution of this article is in its utilization of a broader approach to HC theory.

Research Questions

Although many researchers utilize the variable of education as a default variable of HC, others have suggested that education is not the only variable to comprise HC (Becker, 1964; Heckman, 1995, 2000; Heckman and Cunha, 2007; Schultz, 1981). According to OECD (1998), it is important to see human capital as a multi-faceted set of characteristics, and investments and their potential results as being equally heterogeneous… It has become evident that simplified proxies for human capital formation such as years of initial schooling do not on their own adequately measure the creation of necessary skills and competencies, and that only a wider definition can provide clues about where investment is most needed. (p. 8) Further, according to OECD (2001), while human capital has often been defined and measured with reference to acquired cognitive skills and explicit knowledge, a broader notion of human capital, including attributes, more adequately reflects how various non-cognitive skills and other attributes contribute to well-being and can be influenced and changed by the external environment including learning. (p. 18) These attributes and non-cognitive skills may be lacking in people regardless of their education or social class. The entire society may be suffering from underdevelopment of some of them. This suggests that, to improve the level of HC, not only improvement in education is required. Improvement of other factors that comprise HC is necessary as well. Verkhohlyad (2008) suggested inclusion of the following variables, together with educationrelated variables, as part of NHC: national identity awareness, character most widespread in a country’s population, and family strength. In this article, we study the role of national identity awareness as it relates to NSC, suggesting that an increase in the level of national identity awareness may be associated with an increase in national cohesion and, therefore, in order to increase NSC, an increase in the level of national identity awareness is required. Therefore, the research questions are as follows:

Research Question 1: Is the level of education in a country associated with the level of NSC in that country?

Research Question 2: Is the level of national identity awareness among people in a country associated with the level of NSC in that country?.

Research Question 3: Is using the measures of education and national identity awareness in a country’s population a better predictor of the level of NSC than either measure alone?

Methods

Proxy for social cohesion

Numerous variables have been named to proxy for social cohesion. The most wide-spread proxies that have been used are: membership rates of organizations and civic participation (Guiso, 2000; Helliwell and Putnam, 1995; Knack, 2003; Krishna, 2002; Putnam, 1993); measures of trust (World Value Survey, Knack, 2001; La Porta, 1997; Rose, 1995); income distribution measure (Easterly 2001; Easterly, Ritzen, Woolcock, 206; Rodrik, 1999); ethnic heterogeneity (Mauro, 1995). Following the suggestions of Easterly (2001), Easterly, Ritzen, Woolcock (2006), Rodrik (1999), as well as the British Report, this article suggests using the income distribution meausure – i.e. the share of national GDP among different socio-economic classes factor – as the proxy for social cohesion in the country.

Proxy for national identity awareness

National identity may be defined as the citizens’ view of the factors that unite the population of a country into a single community and that differentiate that community from others (Shulman, 2005). According to Webster’s dictionary, a nation is a community of people composed of one or more nationalities and possessing more or less defined territory and government. According to other definitions, a nation can be described as a community of people obeying the same laws and institutions within a given territory (Smith, 1991). This implies some common institutions and a single code of rights and duties for all members of the community. This presupposes a measure of common values and traditions among the population (Smith, 1991) – “in other words, nations must have a measure of common culture and a civic ideology, a set of common understandings and aspirations, sentiments and ideas, that bind the population together in their homeland” (p.11). Historic territory, common institutions, legal-political equality of members, and common civic culture and ideology comprise the standard model of a nation (Smith, 1991). Consequently, national identity is awareness of these features and their functions. It is awareness of these commonly held rules and norms, and the appreciation and support of them. Therefore, the National Identity Awareness variable can be presented as a combination of the following factors (Verkhohlyad, 2008):

- Common norms, values, and culture shared by a country’s population

- Perception of collective destiny (goals) among people in a country

- Common institutions/rights and duties for all members of a society

- Perpetuation of common myths and historic memories among citizens of a country

As suggested in Verkhohlyad (2008), with Factor Analysis applied, these factors may be operationalized as a function of the following indicators, which are publicly available for most of the world countries:

- Common Institutions/Rights and Duties for All Members

Government Effectiveness measure

Voice and Accountability measure

Corruption Perception Index

School life expectancy

Level of total government consumption minus Military expenditure as percent of GDP - Common norms, values, and culture

Linguistic cohesion

Ethnic cohesion

Religious cohesion - Collective Goals (Awareness of Collective Destiny)

Number of holidays that the country celebrates

Gini Coefficient

Number of Olympic medals (1998–2005) - Perpetuation of common myths and historic memories

Time of Independence

Number of Nobel Prize laureates in a country (1901–2005)

Data Analysis

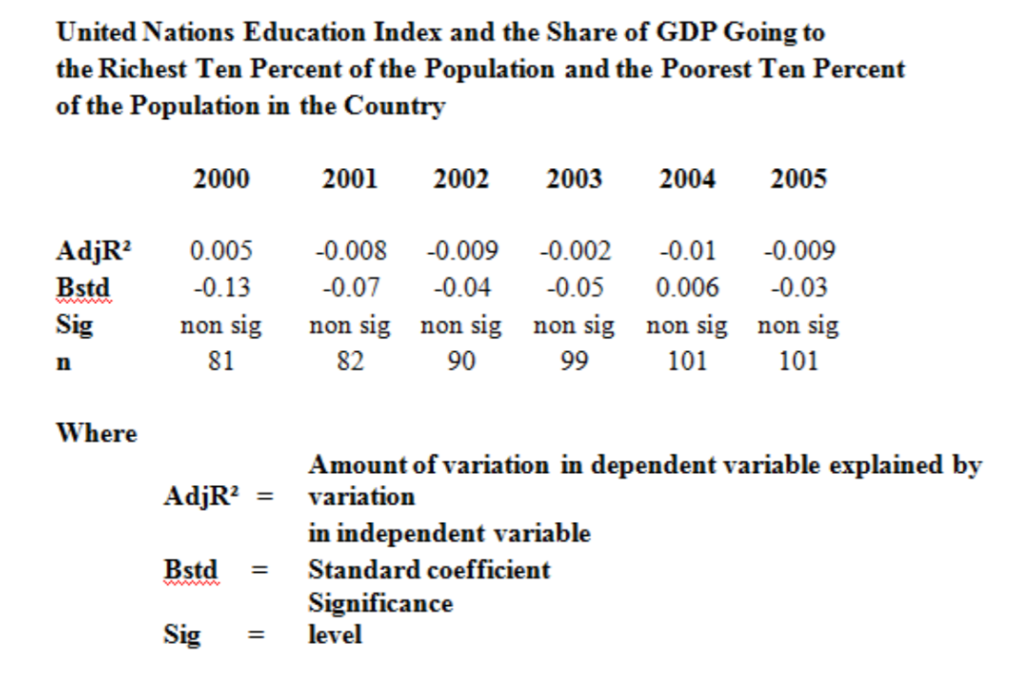

Research Question 1: The level of education in the country is not associated with the level of NSC in this country. To test this research question, relationship between two variables was analyzed: the Share of GDP among different socio-economic groups (a proxy for social cohesion in the country) as a dependent variable and UN Education Index which is a composite of the adult literacy rate and combined primary/secondary/tertiary gross enrolment ratio (as an independent variable). Human Development Reports published by the United Nations (UN, 2000-2008) were the source of both variables. The higher the factor of the Share of national GDP among different SE groups in a country, the more dispersed and non-cohesive the society is. High number of the factor of the Share of national GDP among different SE groups in a country shows that the difference between what the poor and the rich get is high. Data for six consecutive years (2000-2005) was utilized. Although the researcher did their best to find data for all the world countries with population of 100,000 and more, not all countries have their data available. Applying simple regression analysis to these two variables provided evidence for non-significant relationship between them (Tab. 1). This may suggest that there is no or very week relationship between the level of education in the country and the level of NSC in this country.

Research Question 2: The level of national identity awareness among people in the country is associated with the level of NSC in this country. Increase in the level of national identity awareness sub-factor of NHC is associated with increase in NSC.

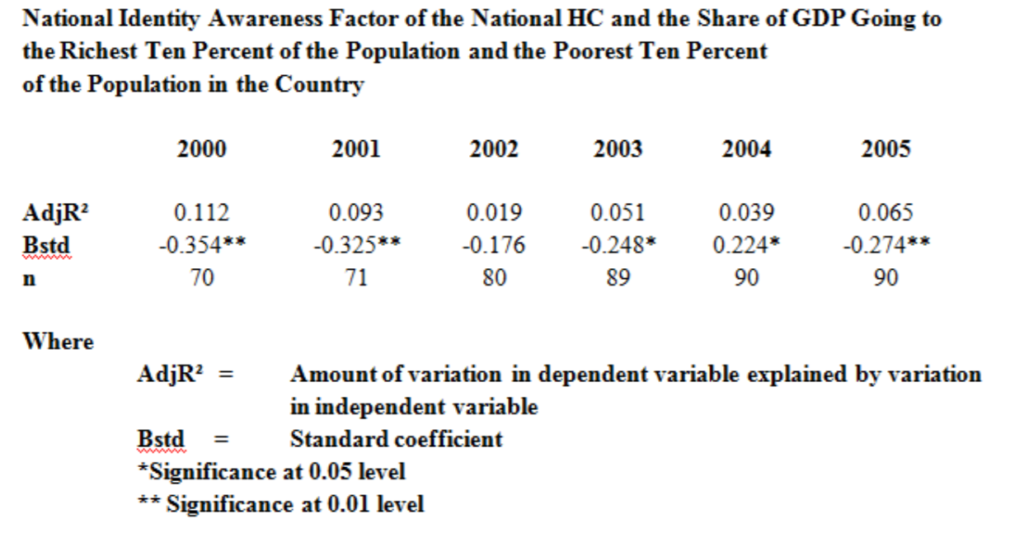

Relationship between two variables was analyzed: the Share of GDP among different socioeconomic groups (a proxy for social cohesion in the country) as a dependent variable and National Identity Awareness factor of the NHC as an independent factor. Human Development Reports published by the United Nations were the source of the dependent variable (UN, 2000–2008) and assessment of Verkhohlyad (2008) was the source of the independent variable. The higher the factor of the Share of national GDP among different SE groups in a country, the more dispersed and noncohesive the society is. High number of the factor of the Share of national GDP among different SE groups in a country shows that the difference between what the poor and the rich get is high. Applying simple regression analysis to these two variables provided evidence for significant negative relationship between them. As reported in Table 2, increase in 1SD of the National Identity Awareness factor on average led to 0.27SD decrease in the inequality measure. One standard deviation increase in the national identity awareness variable is associated with 0.27 standard deviation decrease in the difference of the portion of national GDP going to the poor and the wealthy in the country. More specifically, in 2000, 1 SD increase in national identity awareness variable associated with 0.35SD decrease in the difference of the portion of national GDP going to the poor and the wealthy in the country. In 2001, the decrease in such difference was 0.33SD, in 2002 – 0.18SD, in 2003 – 0.25SD, in 2004 – 0.22SD, and in 2005 – 0.27SD. As reported in Table 2, variation in the National Identity Awareness factor of the National HC on average accounts for 6.3% of variation in the inequality measure of the Share of GDP among different socio-economic groups factor.

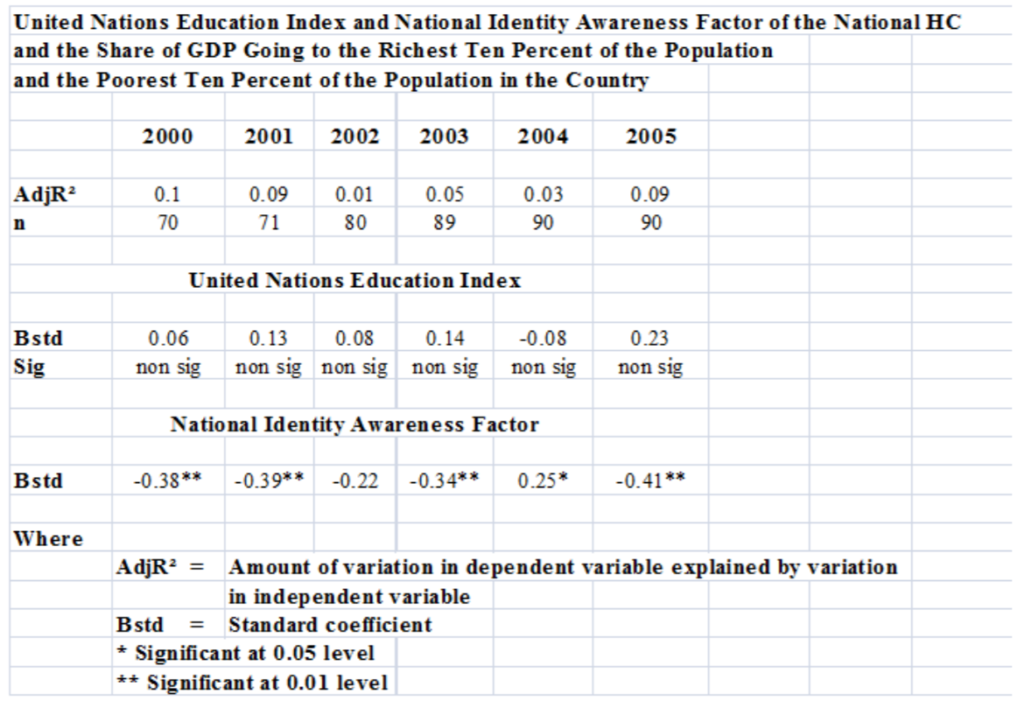

Based on the provided statistical results, we can say that social cohesion in a country may increase with the increase in the National Identity Awareness factor in the population of this country, including all its social classes – elite and wealthy segments alike. Research Question 3: Utilizing the measures of education and national identity awareness in a country’s population is a better predictor of the level of NSC than only education measure. To test this research question, multiple regression analysis was conducted with the Share of GDP among different socio-economic groups (a proxy for social cohesion in the country) as a dependent variable and National Identity Awareness factor of the NHC and UN Education Index, as independent factors. According to the analysis’ results reported in Table 3, the variable of education continues to be non-significant, while the variable of national identity awareness continues to be significant.

Conclusion

The importance of strong NSC for a country’s socio-economic development is hard to exaggerate. Strong social cohesion is associated with strong national institutions, good economic and social development of the country. The HC theory provides meaningful insight about strengthening of NSC. According to this article, national identity awareness sub-factor of the NHC is strongly positively correlated with the state of NSC in a country. Consequently, to strengthen NSC, it’s necessary to increase the level of national identity awareness in the country. It’s not just division between the poor and the wealthy that leads to decrease in social cohesion. This division is the result of general lowering of national identity awareness in many people in the country regardless of their socio-economic status. Simply raising the level of education in poorer segments of the country with the goal of raising NSC will not help, if this step is implemented by itself. National identity awareness level needs to be raised in all people. With such steps implemented, a society may become a more socially cohesive society. For such a society this may mean increase in economic development, increase in abilities to deal with economic downfalls, increase in social health and many other positive outcomes.

Implications for Practice and Policy

Unless some targeted steps are taken, NSC will continue to deteriorate in many countries. After establishing relationships between national identity awareness and NSC, it is necessary to discuss the practical issue of national identity awareness’ development. How can this quality be developed in people? Policy analysts in countries need to utilize their knowledge of their specific national culture, mentality and history to achieve this goal.

Implications for Future Research

According to the HC theory, the economic value of HC has two dimensions: HC economic benefits to its owner (private return on HC) and HC economic benefits to the national economy and community (public return to HC) (OECD, 2001). From the perspective of a HC owner, HC’s value lies in financial return on investment into HC, which most of the time is displayed by increased earning and improved welfare of the individual (Becker, 1964, 1993; Schultz, 1961, 1971, 1981). From the perspective of the community, individual’s HC’s value lies in fueling of economic growth via higher productivity, creation of opportunities for economic development, taxes paid, knowledge spillovers and so on. Economic benefits are not the only benefits that HC provides, as improvement of health, increase in socially responsible behavior, social citizenship are important non-financial benefits of HC. We can say that the benefits of an individual’s HC for a society in large are seen via financial and non-financial factors. Although most of the time public return to HC of in financial terms is fulfilled by paying taxes, providing jobs and other ways of economic development, it seems like the non-financial contribution (for example, nation building, participation in a biggercommunity activities, etc) is not fully accomplished, although it has great value. It would be interesting to see what opportunities for increasing of the NSC lie in people in the country’s more active sharing of their non-financial return to HC with the bigger communities.

References:

- Alesina, A., Devleeschauwer, A., Easterly, W., Kurlat, S., & Wacziarg, R. (2003). Fractionalization. Journal of Economic Growth, 8, 155-194.

- Alesina, A., & La Ferrara, E. (2000). Participation in heterogeneous communities. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 115(3), 847-904.

- Annett, A. (2000). Social fractionalization, political instability, and the size of government. Retrieved from http://ssrn.com/abstract=879607

- Becker, G. 1964. Human capital. New York: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Becker, G. 1993. Nobel lecture: The economic way of looking at behavior. Journal of Political Economy 101: 385- 409.

- Bossert, W., D’Ambrosio, C., & LaFerrara, E. (2006). A generalized index of fractionalization. ftp://ftp.igier.unibocconi.it/wp/2006/313.pdf

- Council of Europe. (2005). Concerted Development of Social Cohesion Indicators: Methodological Guide. Council of Europe Publishing: Belgium.

- Dragojevié, S. (2001). “Social cohesion and culture: contrasting some European and Canadian approaches and experiences.” Culturelink Review, no. 33/April 2001. Retrieved April 15, 2012, from http://www.culturelink.org/review/33/cl33dos.html

- Easterly, W. (2001). The middle class consensus and economic development. Journal of Economic Growth, 6(4), 317-335.

- Easterly, W., & Levine, R. (1997). Africa’s growth’s tragedy: Policies and ethnic divisions. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 111(4), 1203-1250.

- Easterly, W., Ritzen, J., Woolcock, M. (2006). Social Cohesion, Institutions, and Growth. Economics and Politics, 18(2), p. 103-120.

- Guiso, L., Sapienza, P., Zingales, L. (2000). The Role of Social Capital in Financial Development. NBER Working Paper No. W7563, Cambridge, MA.

- Heckman, J. (1995). Lessons from the bell curve. Journal of Political Economy, 103(5), 1091-1120.

- Heckman, J. (2000). Policies to foster human capital. Research in Economics, 54, 3-56.

- Heckman, J., & Cunha, F. (2007). The technology of skills formation. Paper presented as American Economic Association Conference. Chicago, IL: Jan 5-7.

- Helliwell, J., Putnam, R. (1995). Economic Growth and Social Capital in Italy. Eastern Economic Journal, 21, p. 295-307.

- Helliwell, I. F. (2001). The Contribution of Human and Social Capital to Sustained Economic Growth and WellBeing: International Symposium Report, Human resource Development Canada and OECD. Retrieved from

- http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/25/10/1825902.pdf

- Hyrych, I. (2012). Viacheslav Lypynsky; Champion of Conservatism. The Ukrainian Week, 10(33), p. 38–41.

- Retrieved June 25, 2012, from http://ukrainianweek.com/History/53202

- Inglehart, R. (2004) Human beliefs and values: A cross-cultural sourcebooh based on the 1999–2002 values surveys, Mexico: Siglo Editors.

- Jeannotte, S. (2003). Social Cohesion: Insights from Canadian Research. Presented on the conference on social cohesion. Hong Kong, Nov 29, 2003. Retrieved July 5, 2012, from

- http://www.socsc.hku.hk/cosc/Full%20paper/Jeannotte%20Sharon_Full788.pdf

- Jenson, J. (1998). Mapping Social Cohesion: The State of Canadian Research. Canadian Policy Research Networks Study No. F/03.

- Kaplan, G., Pamuk, E., Lynch, J., Cohen, R., Balfour, J. (1996). Inequality in income and mortality in the United States: analysis of mortality and potential pathways. British Medical Journal, 312, p. 999-1003.

- Kawachi, I., Kennedy, B. (1997). Health and Social Cohesion: Why Care about Income Inequality? British Medical Journal, 314, April 1997, p. 1037-1040.

- Keeley, B. (2007). Human Capital: How what you know shapes your life. OECD Insights. OECD. Paris, France.

- Knack, S. (2001). Trust, associational life and economic performance in the OECD. In J. Helliwell, ed., The Contribution of Human and Social Capital to Sustained Economic Growth and Well-Being (Human Resource Development Canada, Ottawa).

- Knack, S. (2003). Groups, Growth, and Trust: Cross-Country Evidence on the Olson and Putnam Hypotheses. Public Choice, 177, p. 341-355.

- Krishna, A. (2002). Active Social Capital: Tracing the Roots of Development and Democracy. Columbia University Press: New York.

- La Porta, R., Lopez-de-Silanez, F., Shleider, A., Vishney, R. (1997). Trust in Large Organizations. American Economic Review 87, 333-338.

- Mauro, P. (1995). Corruption and Growth. Quarterly journal of Economics, 11(3), 681-712.

- Moller, J. O. (2000). Toward Globalism: Social Causes and Social Consequences (pages 113-132) in The Creative Society of the 21st Century, OECD: Publication Division. France.

- OECD (2011). Education at a Glance. OECD Indicators. OECD Publishing. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/61/2/48631582.pdf on July 5, 2012.

- OECD (2001). The Well-Being of Nations: The Role of Human and Social Capital. Center for Educational Research and Innovation: Paris, France.

- OECD (1998). Human Capital Investment. An International Comparison. Paris: OECD Publications. Retrieved from http://browse.oecdbookshop.org/oecd/pdfs/free/9698021e.pdf

- Phipps, S. (2003). Social Cohesion and Well-Being of Canadian Children. In Lars Osberg, ed. The Economic Implications of Social Cohesion. Toronto: the University of Toronto Press.

- Putman, R. (1993). Making Democracy Work. Civic Traditions in Modern Italy. Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ.

- Reimer, B., Wilkinson, D., Woodrow, A. (2002). Social Cohesion in Rural Canada. Quoted by Battaina-Dragoni, G. (2003). The Council of Europe’s Strategy for Social Cohesion. Conference on Social Cohesion, 28-29 November 2003.

- Ritzen, J. (2001). Social Cohesion, Public Policy , and Economic Growth: Implications for OECD Countries. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/25/2/1825690.pdf

- Ritzen, J., Easterly, W., & Woolcock, M. (2000). On “good” politicians and “bad” policies: social cohesion, institutions and growth. World Bank. Retrieved from

- http://siteresources.worldbank.org/INTWBIGOVANTCOR/Resources/wps2448.pdf

- Rodrik, D. (1998). Where did all the growth go? External shocks, social conflict and growth collapses. NBER Working Paper, No. 6350.

- Rose, R. (1995). Russia in an hour-glass society: A constitution without citizens. East European constitutional Review 4(3), 34-42.

- Schultz, T. 1981. Investing in people: The economics of population quality. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

- Schultz, T. 1971. Investment in human capital. New York: The Free Press.

- Schultz, T. 1961. Investment in human capital. The American Economic Review 51: 1-17.

- Turok, I., Kearns, A., Fitch, D., Flint, J., McKenzi, C., & Abbotts, J. (2006). State of the English cities: Social cohesion. Communities and Local Government Publications: UK. Retrieved April 10, 2012, from http://www.communities.gov.uk/documents/regeneration/pdf/154184.pdf

- United Nations Development Program (2000–2008). DATE. Human development report. New York: United Nations.

- Verkhohlyad, O. 2008. The development of an improved human capital index for assessing and forecasting national capacity and development. Unpublished PhD dissertation. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University.

- Vigdor, J. (2002). Interpreting ethnic fragmentation effects. Economic Letters, 75, 271-276.