- Kyiv School of Economics

- About the School

- News

- KSE Proposal for a Further Package of Oil and Gas Sanctions

KSE Proposal for a Further Package of Oil and Gas Sanctions

13.01.2023

Ahead of the February 5th launch of the EU oil products embargo and introduction of product price caps, we propose an ambitious package of new oil and gas sanctions:

1. cutting the crude price cap to $50/bbl at the January review;

2. setting the product price caps at a level consistent with the crude cap and pre-invasion product price variance to the crude benchmark;

3. banning imports of Russian gas into the EU via pipelines controlled by Russia, thereby closing Turkstream and sending gas via Ukraine’s GTS;

4. banning imports of Russian LNG into the EU;

5. imposing full sanctions on Gazprom, Russian oil companies, and Gazprombank, with limited exemptions for oil price cap transactions.

Russia’s position has weakened considerably in recent months. Despite record oil and gas earnings in 2022, the balance of advantage in energy has swung away from Russia, as Europe has adjusted to the loss of Russian gas supply, and gas and oil prices have fallen back to pre-invasion levels. Right on cue, and before the full impact of the price caps, Russia’s underlying financial fragilities have resurfaced with a sharp fall in the ruble and widening of the budget deficit late last year, triggering unplanned debt issuance and sales of reserve assets.

The proposed measures will further reduce Russia’s oil and gas revenues—by about $40 bn in 2023, or roughly a quarter, compared to the status-quo scenario. This would take them to a level which has previously triggered financial and currency crises. And the package can highlight further downside risks, with a threat —credible given Russia’s low production costs and dependency on oil revenues— to take the oil price caps lower at a future review.

Europe’s strong position on gas supply allows it to take a more aggressive stance. A record build in gas storage last year, leading to record storage levels for this time of year, despite the collapse in Russian flows has shown that Europe can live without Russian gas. The priority should now be to squeeze Russia’s gas revenues. We suggest closing down Turkstream and banning European imports of Russian LNG as next steps.

Full sanctions on Russia’s energy firms should accompany these steps. Up until now, Western governments have refrained from imposing full sanctions on Russian energy firms and Gazprombank, given the dependency on Russian supplies and the need to pay for energy imports. Now that this relationship has weakened, Russian oil and gas companies as well as Gazprombank—key agents of the Russian state—should face full sanctions.

We see Russia’s economy as fundamentally fragile going into 2023. It was shielded last year by record oil and gas earnings, but as these have declined, Russia’s fragilities—already on display just after the invasion—have resurfaced. Moreover, Russia’s macro buffers are compromised by sanctions and dominated by illiquid assets, with a chronic shortage of convertible FX and limited capacity to fund a deficit. We argue that aggressive further steps on oil and gas—such as this package—can significantly exacerbate Russia’s challenges and help shorten the war.

Next Steps on Russian Oil and Gas Sanctions

By Jacob Nell, Borys Dodonov and Ben Hilgenstock

Further decisions on sanctioning Russian oil and gas now need to be made, with the January review of the crude price cap and the need to set the initial price caps on Russian petroleum product exports by February 5th. In this paper, we argue for a further package of oil and gas sanctions to increase the pressure on Russia, including: a) cutting the crude price cap to $50/bbl from February 5th; b) setting the product price caps on February 5th at a level consistent with the $50/bbl crude price cap and the pre-invasion product price variance to the crude benchmark; c) banning imports of Russian gas into the EU via pipelines controlled by Russia, closing Turkstream; d) banning on imports of Russian LNG into the EU; e) imposing full sanctions on Gazprom, Russian oil companies and Gazprombank, with limited exemptions, principally for oil price cap transactions. We estimate these measures will reduce Russian oil and gas revenues in 2023 by about $40 bn, increasing financial pressure on Russia – already showing signs of stress with a sharp fall in the ruble and widening in the deficit even before the price caps bite – and constraining its ability to wage war on Ukraine.

Russia’s oil dependency

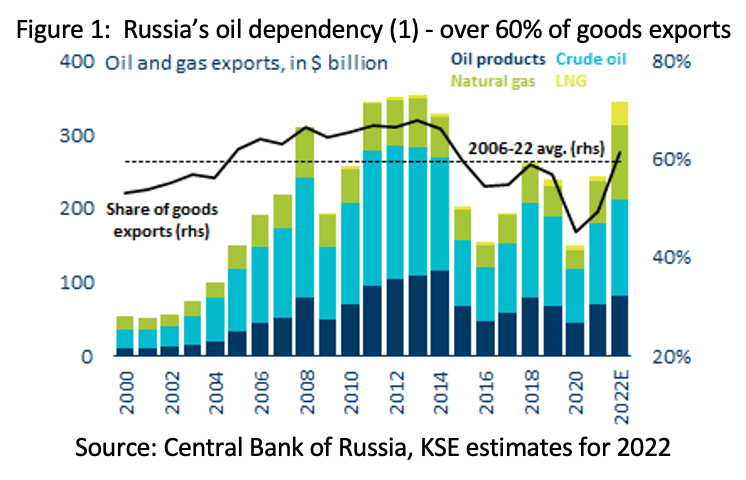

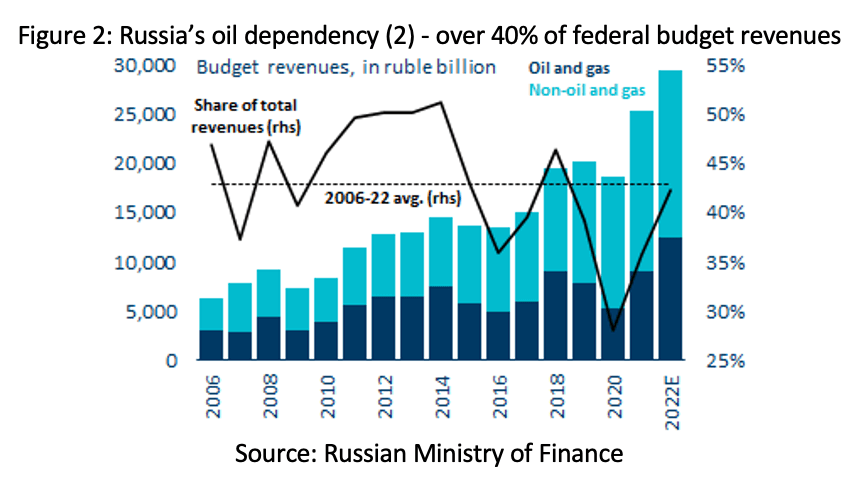

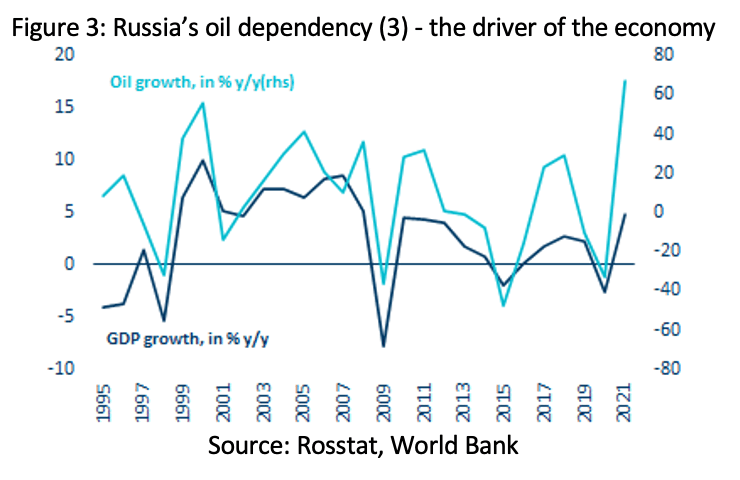

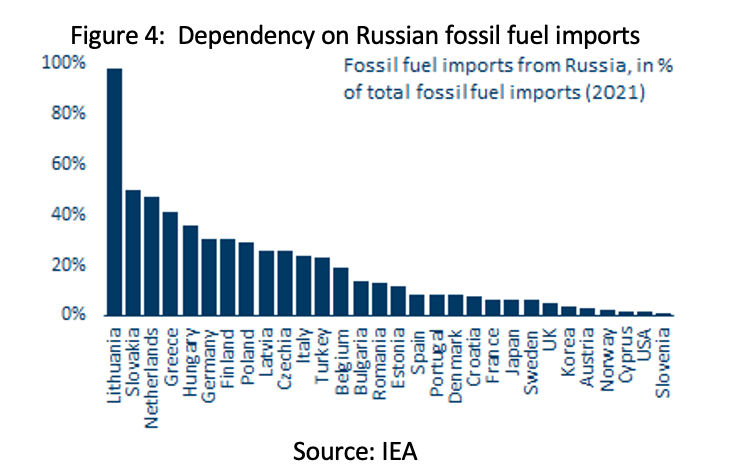

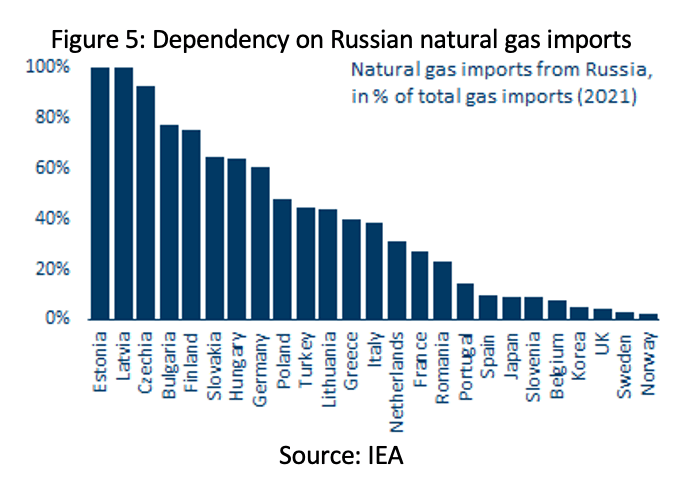

Russia is heavily dependent on oil and gas. It underpins its external and fiscal accounts, accounting in recent years for over 60% of its exports (Figure 1) and over 40% of federal budget revenues (Figure 2), and it drives the economy (Figure 3). At the same time, dependency on Russia for energy has given Russia leverage, particularly in the supply of natural gas to Europe (Figures 4 and 5).

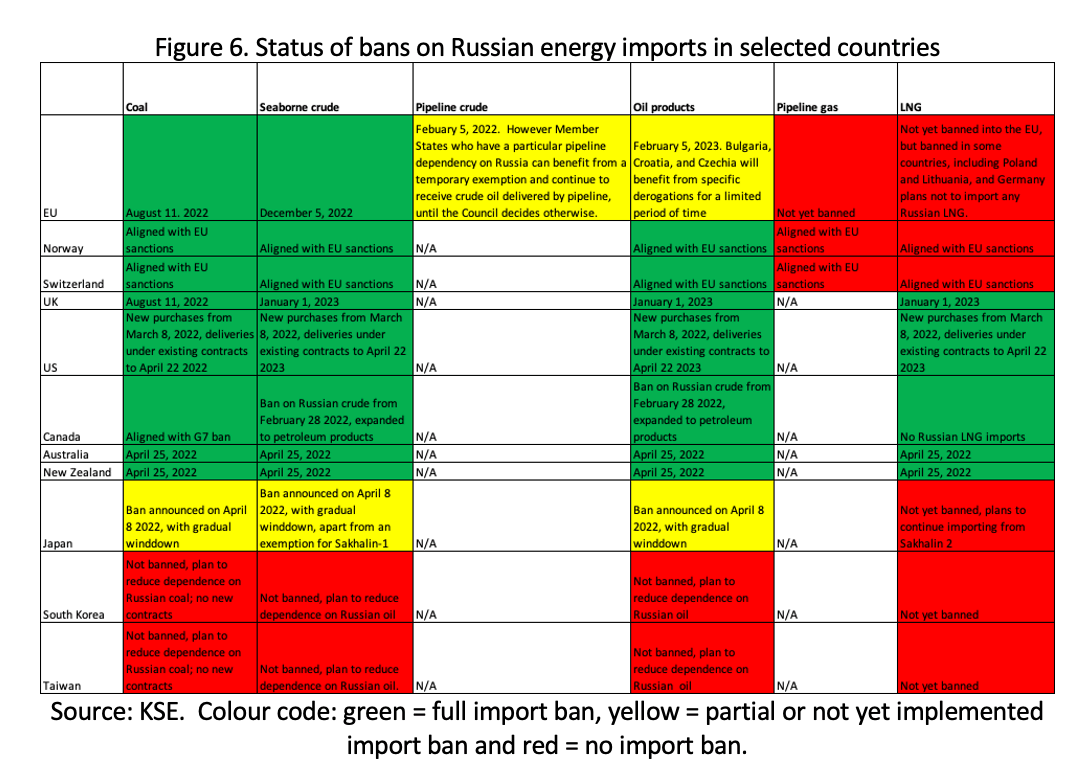

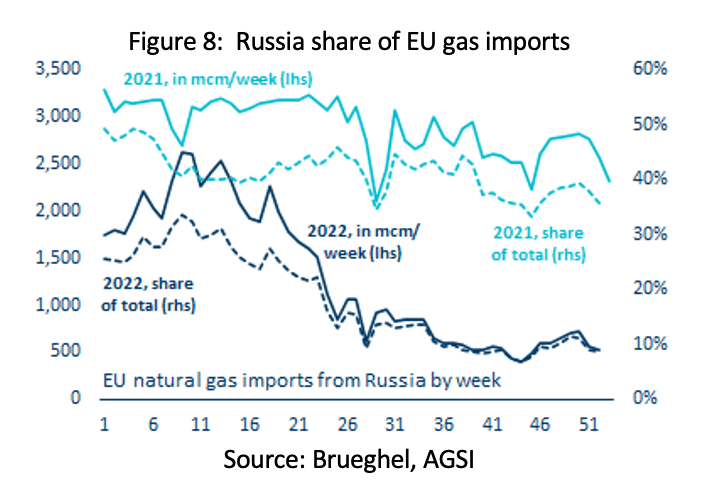

Action on both sides. During the war, both sides have sought to use this situation to their advantage. Russia sought to constrain and influence Europe by squeezing its natural gas supply first covertly from mid-2021, and then overtly after the war had started, first by banning sales to particular countries and then by ceasing to send gas through the Yamal and NordStream pipelines. Ukraine’s allies in turn have made considerable progress in reducing their purchase of Russian energy imports, and in banning them (Figure 6). Take Europe, for example, the most important market for Russian energy. It banned coal imports from Russia in summer 2022 and from December 2022, and is planning to ban pipeline crude and petroleum product imports from February 2023, with certain modest exemptions, mainly for crude for refineries along the southern Druzba pipeline and Bulgaria. It has also reduced its purchases of Russian pipeline gas by around 85%. Further, in concert with allies in the G7 and beyond, Europe has implemented an oil price cap at $60/bbl, requiring Russia to sell its crude for $60/bbl or less if Russia wishes to make use of oil-related services – eg shipping, broking, and insurance – from Western companies. Nonetheless, there remain large gaps in the sanctions Ukraine’s allies have imposed on Russian energy, notably with respect to European gas imports, both pipeline and LNG, and East Asian Russian energy imports.[1]

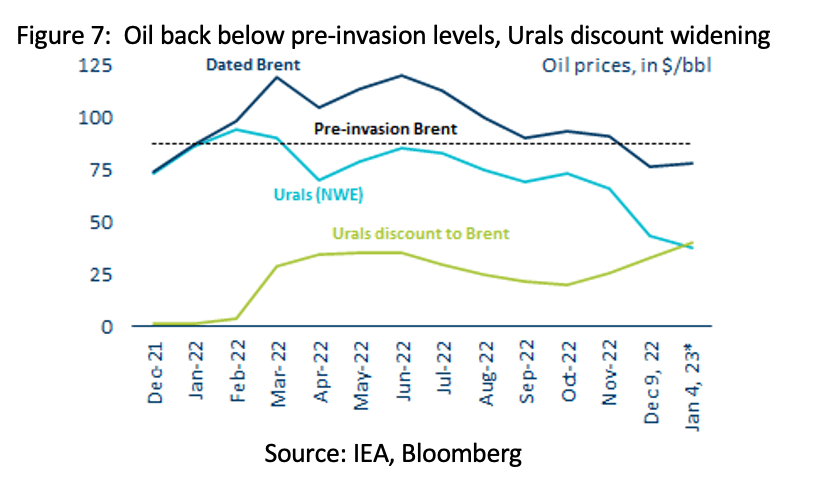

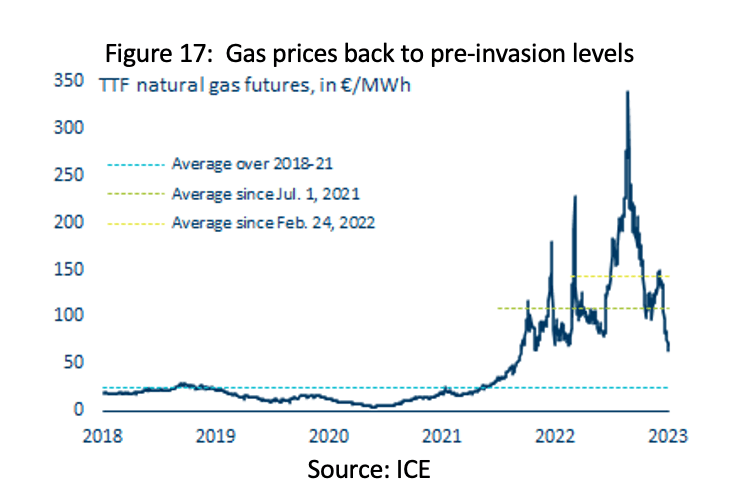

Balance of advantage shifting away from Russia. Initially, Russia had the advantage, benefiting from a surge in oil and gas prices on the invasion and its squeeze on European gas supply. On our estimates it secured record oil and gas revenues in 2022, at least in nominal terms. However, by the end of the year, the advantage had swung away from Russia, as the oil price cap has reinforced the discount on Russian oil (Figure 7), Europe has adjusted to the loss of Russian gas supply (Figure 8), and gas and oil prices fell back to pre-invasion levels.

In this piece, we propose the next steps on sanctioning Russian oil and gas to squeeze Russia’s revenues, and support Ukraine in securing its territory and frustrating Russia’s attempt to redraw borders by force. In an annex, we also map out potential end-states for Russian oil and gas.

We assume that the objectives of the coalition are to:

a) Reduce Russian oil and gas revenues, constraining Russia’s ability to wage war;

b) Eliminate dependence on Russian energy, particularly in Europe;

c) Minimise the risk of a Russian supply shock in global oil and gas markets, which could squeeze growth and drive inflation.

What next?

Four steps to squeeze Russian oil and gas revenues. We propose four steps which in concert will, we think, reduce Russian oil and gas revenues by around $40 bn in 2023, and put Russia firmly on track for our bull case scenario – as set out in the December Yermak-McFaul group paper on implementing the oil price cap – which involves reducing Russia’s 2023 oil and gas receipts by more than two-thirds, to around $100 bn. They comprise a further cut in the crude price cap, petroleum price caps aligned with the lower crude price cap, closure of the Turkstream gas pipeline, and a ban on Russian LNG imports into Europe. We also urge Ukraine’s allies in the East Asian democracies to make more specific and ambitious commitments to end Russian energy imports. Additionally, we propose broad sanctions on Russian energy firms and Gazprombank, since the reason for exempting them – Western dependence on Russian energy – has been effectively resolved.

Next steps on oil

Two major decisions on oil price caps are due in January. Specifically, the G7+ coalition has agreed to a January review of the initial determination of a $60/bbl cap on crude oil, and has to set the cap on oil product prices, which will come into force on February 5.

Reasons why the crude price cap can be lowered (1) – low cost of production. First, while we agree with the policy intention of preserving the incentive to supply, this incentive is strong at price cap levels far below $60/bbl. We believe that Russian average production costs are low, in the $10-15/bbl range, since Russia’s oil fields are typically large, supporting a low cost per barrel of production, and benefit from existing infrastructure and workforce. Moreover, we would base the estimate of production costs on opex, and not include any allowance for recovery of capital investment or payment to equity holders, since during the war those payments can be suspended: for instance, the Russian government suspended the Gazprom dividend earlier this year while levying a special one-off tax to capture some of the excess profits from high gas prices for the government. Hence, even a price cap of $30-35/bbl, as suggested by the Yermak-McFaul group, would maintain a strong incentive to supply for most Russian production.

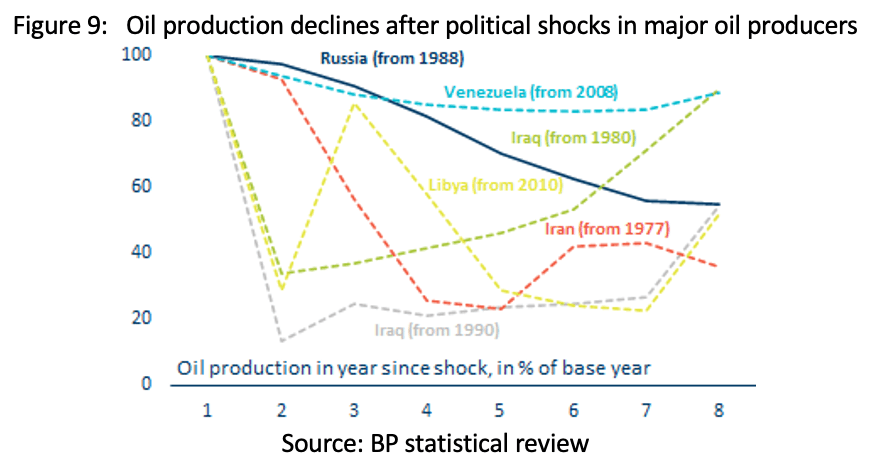

Reasons why the crude price cap can be lowered (2) – target average not marginal production cost. Further, we believe it is a mistake to set the price cap with the aim of maintaining the incentive to produce the marginal – ie the most expensive – Russian barrel, since we believe that it is a policy objective that Russian supply should fall over time, as a consequence of sanctions, as has been seen in other countries subject to sanctions, such as Iraq, Iran and Venezuela (Figure 9). In other words, the relevant metric for setting the price cap is average rather than marginal production costs, since the objective of the price cap policy is not to support unchanged Russian supply but to ensure that the decline of Russian supply, and the marginalisation of Russia as an energy supplier to the advanced economies, proceeds without a supply shock, allowing time for alternative supplies to come to market to replace Russian supply.

Reasons why the crude price cap can be lowered (3) – weaker ruble. Finally, Russian production costs are in rubles, and so the dollar cost of production will fall as the ruble weakens, which we expect as Russia’s oil and gas revenues are squeezed. So we would expect the average Russian production cost to fall further as more expensive marginal supply is shut in and the ruble weakens. In theory, this implies that the oil cap price could be brought well below $30/bbl, perhaps to $20/bbl, without undermining the incentive to supply.

Keeping Russia’s oil price below $35/bbl should be enough to constrain its aggression, we think. However, our analysis suggests that Russia will already face major financial strain, and will struggle to prevent a ruble collapse and fund the budget at a sustained oil price cap of $30-35/bbl – which is likely sufficient to constrain Russia and support Ukraine to achieve its objectives. To implement this, we would propose as the next step a meaningful cut in the crude price cap in the January review of $10/bbl to $50/bbl, scheduled to come into force concurrently with the petroleum product price caps on February 5th, and committing to a further review in March and guiding to a further cut at that March review.

Next steps on petroleum products

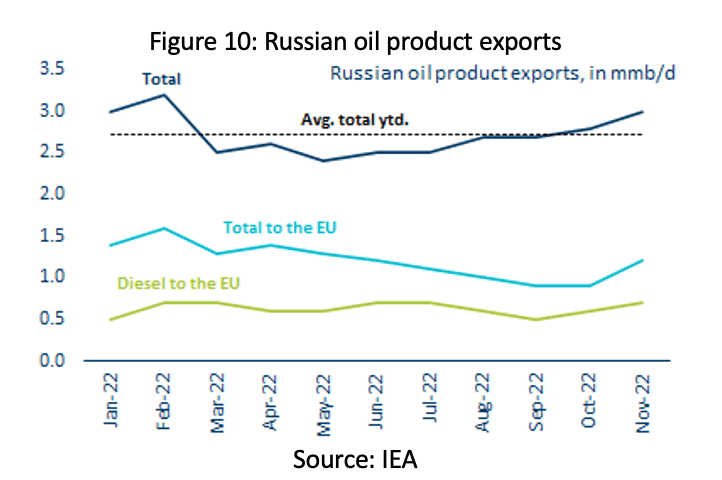

Importance of product price caps. The petroleum product price caps are not just a technical sideshow, for two reasons. First, an unusually large proportion of Russia’s total oil exports – around a third – are in the form of products, with exports of diesel being particularly important. Second, the countries which have served as key destinations for banned Russian crude – China, India and Turkey – have large refining sectors and are less interested in buying product – which helps explain why Rssian product and, in particular, diesel exports to the EU, are relatively unchanged (Figure 10). In fact the slight increase in diesel exports in October-November was due to French refinery strikes, seasonal maintenance and last-minute stockbuilding before the February 5 EU ban on Russian oil product imports. Even so there has been adjustment, with the Russian share of diesel imports to the EU down to 40% in October 22 from the 60% pre-war level.

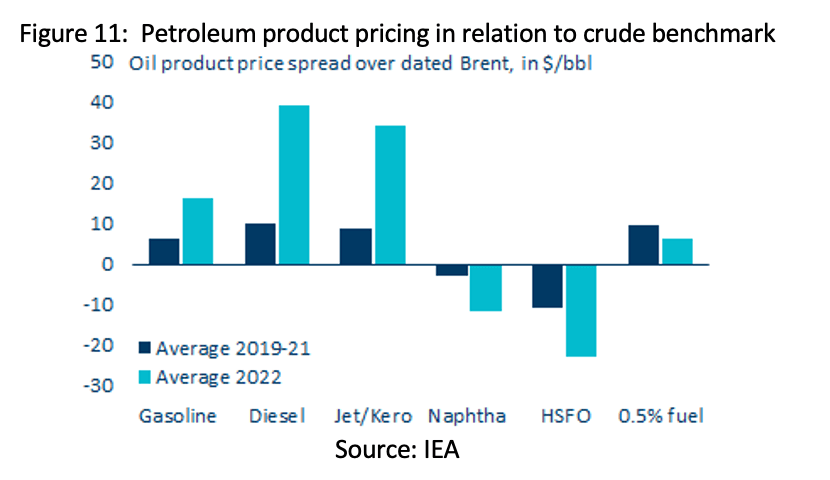

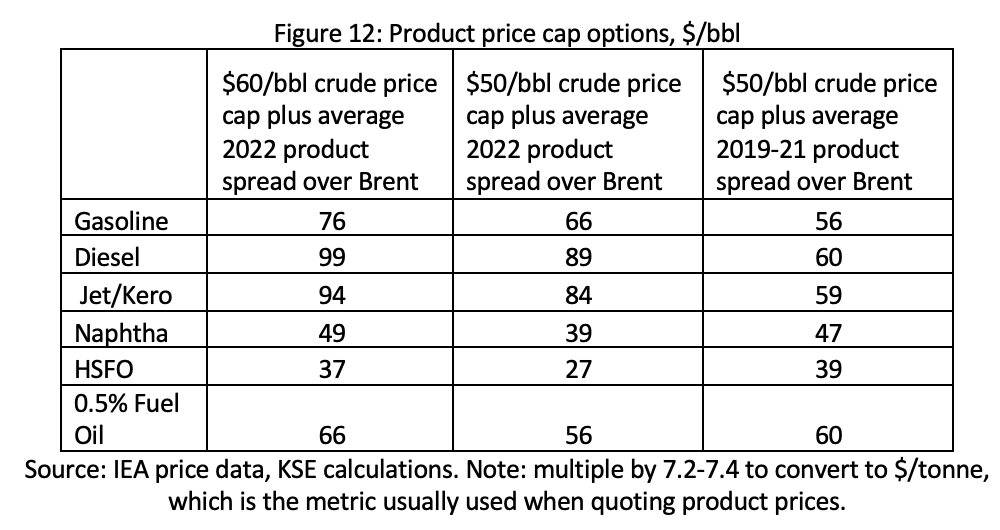

Formula for product price caps – crude price cap plus product-specific adjustment. The most straightforward option for setting the petroleum product price caps would be to set them by reference to the crude oil price cap, plus an adjustment for the premium or discount for the product relative to the crude benchmark. However, most product prices, including diesel and jet, have traded at an enhanced premium to benchmark crude since the invasion (Figure 11). Consequently, the product price cap could be set to include the enhanced premium since the invasion, or it could be set on the basis of the pre-invasion relation of crude to diesel prices. These options are priced in Figure 12.

We favour the tougher option, but also see a case for a more gradual approach on diesel and a more aggressive approach on naptha. In line with our view that Russia is in an increasingly fragile financial position, and pressure should be maximised in the near term to support Ukraine to achieve its objectives, we favour the tougher approach of setting the prices on the basis of a lowered crude price cap and in line with the more modest 2019-2021 product spread over the crude benchmark. At the same time, we can also see that there is a stronger case for a more cautious approach on diesel than on other products, given Europe’s high dependency on Russian diesel supplies. Similarly, we see a stronger case for a more aggressive approach in the first determination of petroleum product price caps for petroleum products – notably naptha – which are relatively easier to substitute, and which has been trading weaker since the invasion than previously. This would hit revenues and disrupt Russian refining, at relatively low cost, and can be used to send a signal about the target level of the crude oil price cap. For instance, the coalition should consider setting fuel oil and naptha prices consistent with a crude oil price of $30/bbl in the initial determination of product price caps.

Next steps on gas

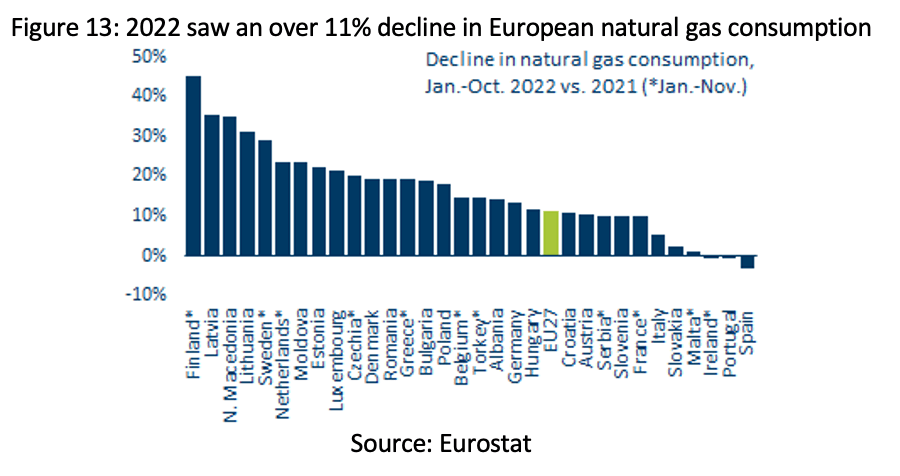

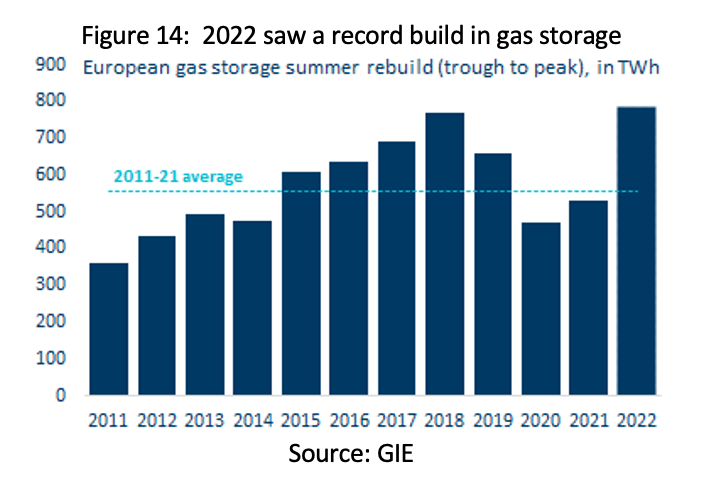

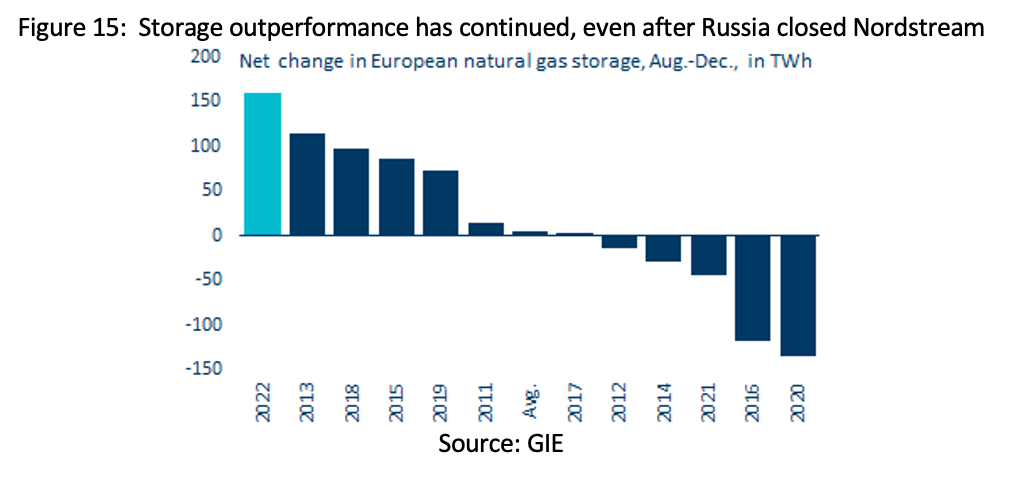

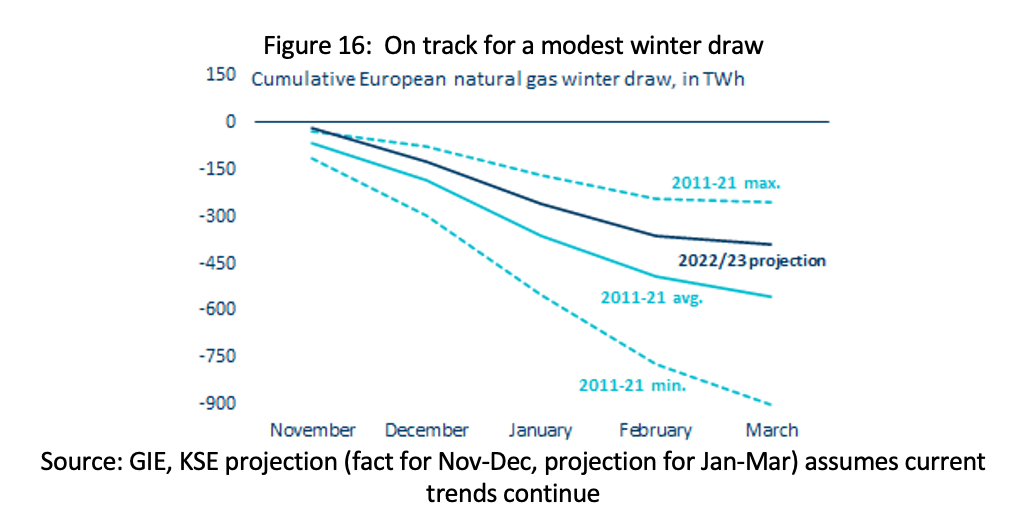

Europe’s strong position on gas supply allow it to now take a more aggressive stance on sanctioning Russian gas. The context here for moving from defensive actions to cut gas demand and increase non-Russian source of supply to offensive actions to cut Russian sources of supply is the extraordinary adjustment seen in European gas and power markets this year. This adjustment can be seen in both demand, which is down 11% YTD, and over 20%Y on the latest data (Figure 13), and in supply, where a surge in LNG supply in particular has offset the decline in Russian gas flows. Perhaps the best barometer of this adjustment is storage, where 2022 saw the biggest storage build ever (Figure 14), including a record performance since September, after Russian flows fell to historically modest levels (Figure 15). As a result, storage levels are currently approaching record levels for this time of year, and are set to exit the heating season, on current trends, at a record around 700 TwH, or around 60% full (Figure 16). As the market digests this adjustment, gas prices have fallen below pre-invasion levels and are forecast to stay there through next winter (Figure 17).

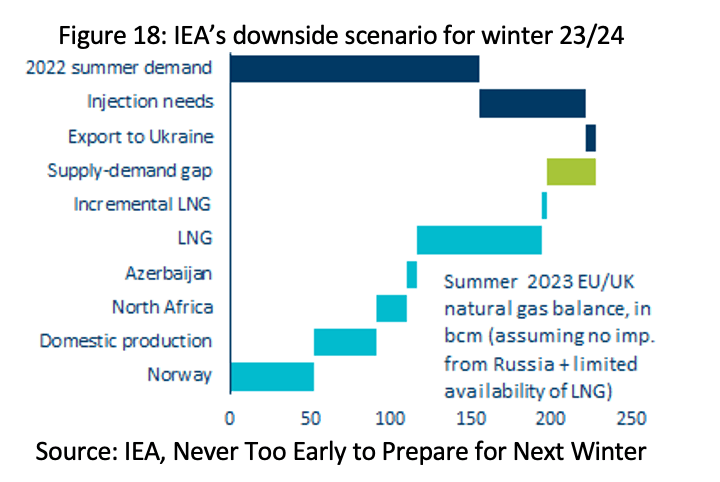

IEA warning about risk to winter 23/24 supply. Despite this strong performance, there are voices of caution. Recently, the IEA has argued that although there is likely enough gas for this winter, they see a risk of a gas shortage next winter in Europe, if Russia cuts off gas supply to Europe totally, and Chinese LNG demand recovers strongly (Figure 18).

We disagree (1) – the risk to next winter is very low. First, we see this as an implausible scenario, for several reasons. Most obviously, the exit level of gas in European storage at the end of this winter is likely to be around 400 TwH or one third higher than last year, implying a much reduced need to rebuild storage – in fact European storage is likely to be full by mid-summer[2]. Second, we see one of the gas market discoveries of 2022 was that when LNG prices are high, many purchasers, particularly in lower-income countries, are willing to reassign term contracts and not bid for LNG – implying that the effective LNG spot market accessible by Europe – in a pinch and at a price – is much larger in practice than on paper. Third, we have seen a dramatic adjustment in European gas and power this year, even with an unfavourable situation in hydro and French nuclear fleet availability – and with both these situations likely to normalise, even as renewable deployment accelerates, we think that Europe can already be confident of avoiding gas shortages next winter as well.

We disagree (2) – the priority now is to squeeze Russia’s gas revenues. Most importantly, however, we are concerned at the risk-averse implications of the IEA’s conservative advice. For us, the overriding objective at the moment is to squeeze Russian oil and gas revenues, which we see as crucial to constrain Russia and shorten the war. And this year’s gas market adjustment, as seen in the data since September when Russian gas flows fell to a modest level – has already demonstrated, we think, that Europe can live without Russian gas. Moreover, the adjustment is not exogenous – as this year has shown, in a crisis situation, extraordinary adjustment, such as building regas terminals in Germany in months rather than years, becomes possible. But absent pressure, and the pace of adjustment is likely to drop. In short, we are opposed to the low-key approach of continuing to buy Russian gas to minimise the risk of a shortage next winter. Rather, we propose to exploit Europe’s rapid adjustment away from dependency on Russian gas and high levels of storage to ratchet up pressure on Russia by taking the initiative and sanctioning Russian gas.

Ban supply from Russian-controlled pipelines. First, we would propose action to restrict further the remaining flow of Russian pipeline gas into Europe. Specifically, we propose that the EU act in accordance with its third energy package, which, among other things, requires Gazprom to separate its production and supply from transmission operations inside the EU, and to allow access to its gas pipelines to third parties.[3] In line with this – and using a similar reason to that used by the German regulator when they refused a licence to NordStream 2 – we believe this gives the EU the power to ban any Gazprom gas exports to the EU via a Gazprom-controlled pipeline. Besides, we think that Gazprom’s abuse of its market power in Europe over the last 18 months was part of a concerted effort by the Russian state to compel Europe not to support Ukraine – and underlines the importance of robust implementation of the third energy package to prevent the accumulation of the market power which can facilitate such abuse. The practical effect of this action will be to put a regulatory block on the EU side to any Russian attempt to relaunch the Yamal or Nordstream pipelines and to close down flows from the Turkstream pipeline. This would in effect ban any Russian gas exports via a Russia-controlled pipeline, and require all remaining Russian gas supply to the EU to flow though Ukraine’s Gas Transmission System. This would enhance Ukraine’s energy security, leverage and revenues, as well as cutting off the risk of a Turkish hub being used to slip more Russian gas into the European market. We note that the GTS can transport up to 140 bcm a year, which is ample capacity at three times the current ca. 40 bcma pace of Russian gas exports to Europe (both pipeline and LNG).

We propose the next step should be Turkstream cutoff, forcing all Russian gas supply to Europe to flow through Ukraine. We are attracted to proposals that all payments for Russian gas sales be made to an escrow account, or that Russian gas sales be subject to a levy, which can then be used to finance Ukrainian reconstruction, or are subject to a price cap. However, based on Russia’s behaviour in aggressively cutting off European countries and halting deliveries via pipelines so far, we assume that Russia’s response to any substantive proposal along these lines will be to cut off all gas flows to Europe, and we see some benefit to Ukraine and its allies to maintaining some Russian gas flow through the GTS in 2023, given uncertainty about Ukraine’s gas supply next winter. So, we propose to focus on the next step in reducing Russia’s pipeline gas sales to Europe for now – ie closing down Turkstream and blocking all Russian attempts to send gas to Europe without going through Ukraine.

…. and a ban on purchases of Russian LNG. Second, we propose that Ukraine’s allies in Europe and East Asia should follow the lead of the US, UK, Canada and Poland, and ban purchases of Russian LNG. Russian LNG sales to Europe last year amounted to 19 bcm, broadly comparable to the level of Russian pipeline flows to Europe since September, and were largely delivered to Netherlands, Belgium, France and Spain, with at least one cargo also delivered to Greece. We would ask for a ban on any new contracts for Russian LNG, and to set a date, eg June 1, 2023, in Europe given the strong supply situation, from which time all Russian LNG deliveries would be banned. While we appreciate that the supply situation in East Asia may be more challenging, given the absence of gas storage on the same scale as in Europe, we see scope for a clear commitment to end purchases of Russian LNG over time, given the planned surge in LNG supply from Qatar, the US and other producers. These measures would release Russian LNG into the wider market, and so would be unlikely to trigger a tighter global LNG market in aggregate, while putting downward pressure on Russian LNG earnings and eliminating residual dependency on Russian energy in Europe and East Asia. In tandem with this LNG embargo, we also urge Ukraine’s allies to explore the opportunity to impose an LNG price cap on Russian LNG, requiring all LNG which uses Western services – ships, insurance, brokers – to be sold under a price cap, as with crude and product.

Russia faces a loss of market, influence and revenues. Russia will be able to find a partial substitute for the loss of advanced economy customers in emerging markets, notably China. Even in oil, Russia will have to offer discounts to secure market share, and will face higher logistics costs, hitting Russian revenues and weighing on volumes. Russian exports of product are likely to shrink in particular, partly since many of Russia’s new core customers – China, India, Turkey – have efficient modern refineries and are exporters of product. In gas, we see a permanent loss of around $50 bn per annum on gas exports to Europe as a plausible estimate. There is no meaningful offset for these lost gas sales since the infrastructure does not exist to redirect pipeline flows from Europe to Asia, and building such infrastructure is expensive and takes years. Besides, the Asian gas price will almost certainly be a fraction of the European gas price, since – as with current pipeline sales to China – Asian buyers will be in a strong position to drive a hard bargain.

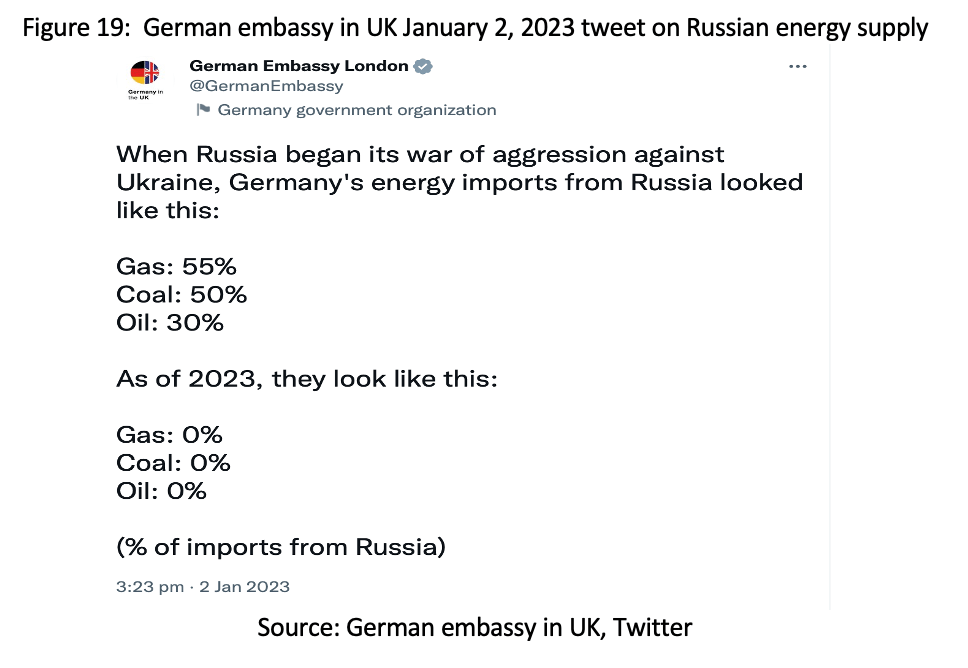

Anticipating Russian retaliation. Russia has shown that it is capable of aggressive and nimble retaliation, often in unexpected ways. In energy, this has included insisting on payment for gas sales in rubles, unilaterally halting flows of gas, often on some technical or safety pretext, and bombing Ukraine’s energy infrastructure. So, clearly a range of retaliatory actions are possible. Russia could withhold all gas supplies to Europe. However, with Europe well stocked with gas, and Russia only supplying at a pace of about 40 bcma at the moment – after Europe reduced its call on Russian gas by 70 bcm in 2022 – we think Russia has largely lost its leverage over the European gas market, as illustrated by the German government tweet copied below (Figure 19). More radically, Russia could withhold all energy supplies including oil, which would likely trigger a supply shock and a global recession. However, we think such a move would hurt Russia more, since it would lose its main source of export earnings and budget revenues, exposing its financial fragility, and constraining its ability to continue the war. Besides, this would most directly hit Russia’s main customers, which are no longer the advanced economies but the emerging markets, who lack a buffer of oil reserves and can be outbid by the more advanced countries. Finally, in the most extreme scenario, Russia could both withhold energy supplies and seek to sabotage other sources of supply to trigger shortages in the advanced economies, in a tactic similar to Russia’s attempt to intimidate Ukraine by bombing its energy infrastructure. However, even in Ukraine this approach does not appear to be working, and implies huge and uncertain financial and military risks, which could for instance unite China, India and the West in seeking to restrain Russia.

Additional sanctions on companies

Full sanctions on Russian energy firms and Gazprombank. Up until now, Western governments have refrained from imposing full blocking sanctions on Russian energy firms and Gazprombank, given Western dependency on Russian energy and the need to pay for energy imports. They have only imposed more specific and partial sanctions, eg a ban on issuing new debt and equity. However, the sharp decline in Western and European dependency on Russian energy now makes it possible to shift to imposing full sanctions, with specific exemptions. We would propose imposition of full company sanctions on all Russian oil and gas companies from February 5th – including state-owned companies such as Gazprom, Rosneft, Gazpromneft, Zarubezhneft, as well as major privately-held oil companies such as Surgutneftegaz and Lukoil – once both the seaborne crude embargo, product embargo and Turkstream ban are in place. We would propose tightly-drawn exemptions for transactions consistent with the oil price caps, the agreed exemptions to the European oil embargo, and sales of Gazprom gas through Ukraine’s GTS, and perhaps for a short transitional period though Turkstream. Further, we would propose imposition of full company sanctions on Gazprombank, the most systemically important Russian bank so far to avoid full sanctions. Now that Russian energy trade with Ukraine’s allies, particularly in Europe, has shrunk to such a modest level, the justification for a broad exemption for Gazprombank lacks merit.

Conclusions

Squeezing oil and gas revenues to put Russia on the back foot and shorten the war. We see Russia’s economy as fundamentally fragile. It was protected last year by record oil and gas earnings, but as these have declined, Russia’s fragilities – on display just after the invasion – have rapidly re-emerged, with a weaker ruble, a wider deficit and rapid erosion of its macro buffers. We propose these next steps – which combined will reduced Russia’s oil and gas revenues by around $40 bn in 2023, while pointing clearly to further action to tighten the oil price caps and squeeze oil and gas revenue[4] – to put Russia into a financially constrained position, and help shorten the war.

Annex: Planning Russia’s future energy trade relations with the West

Ukraine’s allies should think about how to manage the trade relationship with Russia going forward, since a clear view of the end state can help guide the intermediate steps.

We think that there are two fundamentally different states of the world.

In the first – a state of war, whether hot or cold – Russia persists with its revisionist objectives and continues to seek a change of borders (“annexation”), including by the use of force. In such a state of war, whether hot or cold, we see strong reasons for the West to minimise trade with Russia: it avoids dependency on an enemy, and it prevents Russia from deriving revenues or advantage from access to leading markets and advanced technology. In the second, there is a regime change in Russia which leads to a Russian government which accepts existing international borders, and seeks to normalise relations with Ukraine and the West.

The attitude of Ukraine and its allies in the two scenarios, and the long-term perspective for Russia, is fundamentally different. While in a state of war with Russia, the West and Ukraine have a strong interest in maintaining and strengthening sanctions to keep Russia isolated and weak. Once relations are normalised, both will have an interest in Russia succeeding – provided there are adequate constitutional, legal and political reforms to protect against a future return to a revisionist and aggressive regime – and hence in lifting sanctions over time. So in this scenario, we would expect a return of some of the Russia-West trade which has been lost since the invasion, given the established infrastructure and cost advantage. However, we expect this would only be a partial return, partly since Europe and other counterparties will wish to avoid slipping back into a risky level of dependency on Russia, and partially since all countries are committed to net zero and transitioning away from using fossil fuels in the years ahead. Moreover, we would expect the normalisation to be gradual, since Russia will need to establish a track record to build trust, implying sanctions will only be lifted gradually.

Across both scenarios – more fully and permanently in war and more partially and temporarily in peace – we would expect the following impacts:

• a reorientation in Russian trade from Western countries to China and other emerging markets;

• a loss of exports, especially pipeline gas and oil to Europe, as location, lack of infrastructure and lack of established relations hinder Russia’s capacity to redirect exports;

• a loss of access to advanced technology, expertise and capital, as a result of reduced exposure to Western markets and companies, lowering Russia’s trend growth;

• an asymmetric outcome, with the shock to Russian trade and investment leading to a sustained and major loss of Russian growth, plus a high risk of a major financial crisis. By contrast, we see only a limited further impact on the West from loss of trade with Russia. Although Europe had to pay more for its energy this year and – to a diminishing extent – will likely have to pay more for several more years, Europe has we think already effectively eliminated its dependency on Russian energy.

• Disposal of Russian assets in the West and tariffs on Russian exports to the West to finance Ukrainian reconstruction and compensation.

To manage sanctions effectively, so that loopholes are minimised and they are maximally effective during the war phase, and so that sanctions are eased in a controlled way in the peace phase, we propose that the West move to a more managed system for trade with Russia, with two main elements:

• A special licencing regime for trade with Russia. In some strategic cases, such as import of Russian gas into Europe, the entity transacting with Russia may be an official body, eg the European Commission.

• For sanctioned exports from advanced countries to third countries, a requirement for enhanced know your customer due diligence – for both banks and companies – to ensure that robust systems are in place to avoid redirection of sanctioned exports to Russia via intermediaries. For instance, Russia seems to be trying to create an environment in Turkey where it can avoid sanctions with impunity, by providing resources to stabilise reserves and the lira, likely in return for the Turkish authorities turning a blind eye to Russian use of Turkish intermediaries to bypass sanctions.

Ideally these arrangements would be coordinated across the sanctions coalition, although it is of particular importance for Europe, which was Russia’s largest trade partner until the invasion.

[1] Separately, the Yarmak-McFaul group has also proposed sanctions on Russian nuclear power. See here.

[2] In fact, full storage is likely to send gas spot prices to a low level for several months towards the end of the summer season, as happened briefly in late 2022. We see this as potentially an excellent opportunity for Ukraine to access some cheap additional gas for winter 23/24, with donor support.

[3] Russia challenged the provisions of the Third Energy Package before the WTO Panel as violating WTO rules, but in 2018 the WTO issued a ruling rejecting the majority of Russia’s claims and reaffirming principles of the third EU Energy Package. https://ec.europa.eu/commission/presscorner/detail/en/IP_18_4942

[4] This is obviously an approximate calculation. Roughly, Russia exports 2.7 bn barrels of crude and product a year, so $10/bbl off the price via the caps is worth $27 bn. Turkstream gas sales were 13 bcm in 2022, so if it is cut by 10 bcm in 2023 and the gas price is $700/mcm, this would reduce revenues by $7 bn. On LNG sales (19 bcm to Europe in 2022), we assume that Russian sales would fall 10%, and that sales would be executed at a 30% discount, which implies a loss of around $5 bn, compared to 19 bcm sales at $700/mcm.