- Kyiv School of Economics

- People

- Stories

- The New Agricultural Support System in Ukraine: Who Really Benefits?

Agricultural support system in Ukraine has been in the process of constant change over the last 5 years. In 2018, the Government of Ukraine allocated a record UAH 6.3 billion of taxpayers’ money to agriculture in the form of various input subsidies. This has not been, however, accompanied with an evidence-based policy discussion, officially stated goals and justification for the support programs. In these circumstances it is virtually not possible to evaluate the efficiency of the support programs. Subsidies, however, always have unintended beneficiaries. In this note we discuss those beneficiaries and show that only a small share of the support ends up in the pockets of agricultural producers.

Agricultural support system before 2017

The agricultural support system has been constantly evolving over the last 5 years in Ukraine. Before 2017 it was mainly tax benefits that made up more than 90% of the total agricultural support. Tax benefits accrued from a so-called single tax (or Fixed Agricultural Tax before 2015 – FAT) and a special value-added tax regime in agriculture – AgVAT (World Bank, 2013).

The FAT is a flat rate tax that has replaced profit and land taxes. Its rate varies from 0.09% to 1.00% of the normative value of farmland, depending on farmland’s type and location. In 2010, the FAT resulted in an average tax payment of only roughly 0.75 US$/ha of arable land that left farm profits in Ukraine essentially untaxed. In 2015, due to a significant increase of the normative value of land, FAT liabilities increased to roughly $US9/ha, which is also very low compared to what the farmers would have paid under the general tax system.

According to the AgVAT regime, farmers were entitled to retain the VAT received from their sales to recover VAT on inputs and for other production purposes at the discretion of farmers. In 2016 and 2017, the AgVAT system was gradually eliminated under the pressure from the IMF and other international donors. In 2015, the benefits from the AgVAT were estimated at UAH 28 bn. The FAT or profit tax exemption is still in place and is expected to continue. Both tax benefits regimes were heavily criticized (see e.g. World Bank, 2013) and were found to be very cost-ineffective in what concerned stimulating agricultural productivity growth and undermining efficiency and productivity improvements in agriculture.

Agricultural support system after 2017

In 2017 the AgVAT tax benefit system was terminated and replaced by the so-called ‘quasi accumulation VAT’ regime. This was no longer a tax benefit system. Agricultural producers (mainly livestock and horticulture producers) were entitled instead to receive budget subsidies proportionally to the VAT transferred to the state budget. The total volume of the program was UAH 4 billion. The program was, though, heavily criticized as such that favored primarily large agriholdings.

In 2018, the volume of budget subsidies to agriculture increased to UAH 6.3 billion, while the eligibility and allocation criteria changed significantly as well. UAH 1 billion out of 6.3 billion was allocated specifically for small farmers (up to 500 ha of farm size). They can receive both grants (non-repayable) and repayable funding. This funding is distributed among the farmers on the competitive basis and is envisaged to compensate for the purchase of inputs in various forms (concession credits, partial compensation of costs of seeds etc).

The biggest share of budget subsidies, however, was allocated for livestock support, i.e. UAH 4 billion:

- 1.2 billion: partial compensation (30% of total cost, but up to 150 million) of the expenditures for the construction or reconstruction of livestock farms, milking parlors or processing facilities.

- If the construction is financed through credit, then the compensation is bounded by 25% and financed from the other livestock support program (the total budget of this program is UAH 1.1 billion). Farms are ineligible to participate in both programs mentioned above.

- 700 million: maintaining or increasing the herd of young cattle, up to 2,500 UAH per head of cattle kept up to 13-month age. Only individuals are eligible to participate in this program.

- 500 million: 1,500 UAH per cow head payment for corporate enterprises per one cow.

- 300 million: partial reimbursement of the costs of the purchase of breeding livestock (up to 50% of the cost, upper boundaries of sums differ depending on the category of livestock, the highest possible amount of reimbursement is up to 24,000 UAH per head of cattle).

- 200 million: credit concession program. Eligible loans should be smaller than 100 mln UAH and farms may be charged an interest at as low as 3%.

The third largest support program is a UAH 945 million program for the purchase of domestically produced agricultural machinery. Under this program, farmers are eligible to get a partial reimbursement of the cost (25%) of the domestically produced agricultural machinery.

Another 300 million UAH is envisaged to support horticulture, i.e. planting of new gardens, vineyards, berry-fields and their cultivation. This program suggests the reimbursement of up to 80% of the cost of planting material, as well as the governmental support for planting new gardens, building laboratory facilities, freezing facilities and purchasing machinery.

All in all, the above programs could be summarized as the so-called input subsidies, i.e. subsidies that decrease the cost of inputs for the farmers. The main problem, however, is that the updated support programs were designed and implemented without an open and evidence-based discussion of the goals and instruments. This is the worst what can happen with such programs as there is no chance to evaluate the efficiency of the allocated taxpayers money whatsoever. But even if we assume that such programs were designed and implemented properly and sustainably, farmers turn out to be the least beneficiaries in case of input subsidies. There are always unintended beneficiaries in such programs, i.e. not every hryvnia of the money taxpayers pay to fund the subsidies ends up in the pockets of farmers, i. e. of the intended beneficiaries of the program. Below we discuss and evaluate this phenomenon (i.e. the distribution of the benefits of the programs to the subsidized) in more detail.

Beneficiaries of agricultural subsidies

Farmers are not the only beneficiaries of the input subsidies. Generally speaking, input subsidies help agricultural producers earn more income than the market would otherwise provide them. They supplement market receipts with payments drawn directly from the state budget – taxpayers. It turns out, however, that not every hryvnia of the extra money that taxpayers pay to fund the subsidies would find its way directly into the income of the intended beneficiaries, – farmers and rural labor and population in general.

The greater share of that money ends up in the pockets of others. Agricultural producers in Ukraine buy most farm inputs from outside the farm and, as a result, input suppliers capture some, usually significant, share of the benefits. In fact, the government frankly admits that, for example, the program for partial compensation of machinery costs is designed to primarily support the domestic producers of agricultural machinery. Some of the benefits accrue to the landowners and to both hired and own labor (via, e.g. higher rental payments, higher salaries etc). Moreover, a significant portion of what taxpayers pay to support farmers disappears in dead weight losses due to the resource misallocation distortions caused by input subsidies. For example, in the presence of an agricultural machinery support program it is highly likely that (especially small) farmers will tend to buy more of the domestically produced agri-machinery (e.g. tractors, plows etc). At the same time, domestically produced machines tend to be of worse quality and lower productivity thus creating productivity losses for the farmers and for the entire sector. This would not happen under the scenario of no support program as there would be no such a ‘nudge’ from the government towards using the agricultural machines of lower quality.

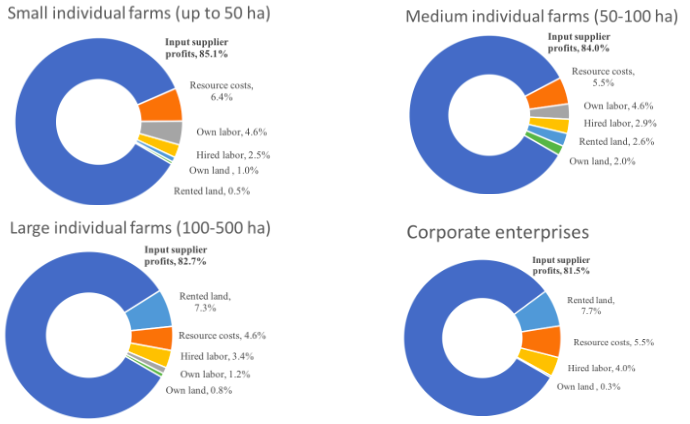

Using the OECD (2002) methodology, we look at the incidence of the budget subsidies and show the major beneficiaries of the agricultural input subsidies in Ukraine. But, in contrast to the OECD approach, where they use aggregate data for the whole European Union agriculture, we distinguish the subsidies incidence between the four groups, small individual farms (up to 50 ha), medium individual farms (from 50 to 100 ha), large individual farms (100-500 ha) and corporate (medium and large) agricultural enterprises. All four groups of farms differ by the intensity of the use of various types of inputs. The main difference, however, is the share of own land in the total volume of cultivated land. Small individual farms tend to cultivate their own land, while larger farms (including the corporate ones) tend to cultivate mainly rented farmland (Nivievskyi et al, 2016).

All specific input subsidies are aggregated into one aggregated input subsidy item and used as a percentage to total revenues in our model calculation. Please refer to the Annex to look at the details of the model calculations. The basic principle of the model is that we calculate production factor earnings and costs caused by the input subsidies programs in a partial equilibrium setup.

The incidence of input subsidies is presented in the Figure 1:

- All four charts demonstrate that input suppliers are the major beneficiaries of the agricultural support program, i.e. they finally receive more than 80% of the budget transfers in all cases. In other words, out of UAH 6.3 billion, input suppliers get roughly UAH 4.8 billion.

- Second largest component is the dead weight losses (resource costs) that the economy incurs due to misallocation of resources, i.e. 5-6% out of UAH 6.3 billion (or roughly UAH 300 million) are simply wasted.

- Landowners make up the second largest beneficiaries of input subsidies, especially when they rent their land to large individual and corporate farmers. In total they receive more than 7% of the total amount of input subsidies; i.e. they top up their incomes by about UAH 500 million.

- And the least well off is rural labor (own and hired), since their additional incomes account for 4 to 7% of the total input subsidies, depending on the farm size.

Figure 1. Incidence of input subsidies for different small farm sizes and for corporate agricultural enterprises.

Source – Ukrainian State Statistics Service, own calculations

Conclusions

Several conclusions can be drawn from the above analysis:

- A quite chaotically evolving agricultural support program is unlikely to help farmers in any way, except probably few mighty and well connected agricultural enterprises. Support programs need to be stable and in place for a significant time span (3-5 years) so that farmers could plan their activities taking into account the state support (see e.g. World Bank, 2013).

- The worst problem with the current state support policy is that it clearly lacks open and evidence-based discussion; goals are not clearly defined and justified and, as a result, the effectiveness of the programs is not possible to evaluate. In normal cases increasing sector productivity and competitiveness should be an ultimate goal of the state support policy, these goals stimulate agricultural growth. Input subsidies in this case is not a good instrument. WTO and applied research suggests that the so called ‘non-distorting’ production and trade support measures (e.g. financing R&D, education, roads and other types of infrastructure, sanitary and phytosanitary measures etc) produce far higher benefits for the sector and for the economy as a whole (see e.g. Demyanenko and Galushko, 2004).

- It follows from the first and the second conclusion that taxpayers’ money is simply wasted. But even if we assume that such programs were designed and implemented properly and sustainably, farmers would be the least beneficiaries in case of input subsidies.

- The various current support programs could be aggregated as input subsidies. It turns out that input suppliers are the main beneficiaries, receiving more that 80% of the entire state support budget (i.e. out of UAH 6.3 billion). 5% to 6% of the program budget is wasted in the form of dead weight losses, and farmers and rural people end up as the least beneficiaries. We argue that this short and aggregated analysis makes the case for revising/abandoning the current support programs and for a better thought-through and evidence-based agricultural support policy design.

Annex

In this paper we applied OECD (2002) methodology for assessing the incidence of input subsidies in Ukraine (or measuring transfer efficiency) using Ukraine-specific data. All the necessary input information for calculations (e.g. the values of supply and demand elasticities) were approximated based on the theoretical considerations and literature review. The ratio of subsidy to price of the input in the model calculations was found as the total volume of subsidies relative to the total inputs production costs. This coefficient was calculated separately for different farm-sizes and corporate farms. Detailed information about calculations is available upon request.

Table 1. Values used in the analysis. Source: State Statistics Service, statistical forms 2-farm and 50-sg, own calculations

| Symbol | Description | Small Farms | Medium Farms | Large Farms | Agricultural Enterprises* |

| S(n) | share of total costs of production attributable to land | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.10 | 0.10 |

| S(l) | share of total costs of production attributable to labour | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.08 | 0.07 |

| n(r) | the proportion of the total land farmed that is owned by farms | 0.68 | 0.43 | 0.09 | 0.04 |

| l(r) | proportion of total labour supplied by farms | 0.65 | 0.52 | 0.27 | 0.00 |

| e(o) | the elasticity of supply of subsidized input | 1.10 | 1.10 | 1.10 | 1.10 |

| e(n) | the elasticity of supply of farm household land | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 | 0.30 |

| e(l) | the elasticity of supply of farm household labour | 0.70 | 0.70 | 0.70 | 0.70 |

| is | the ratio of the subsidy to the price of the input | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.03 |

| S(o) | factor cost share for purchased inputs | 0.77 | 0.74 | 0.72 | 0.72 |

Literature

OECD (2002), “The Incidence and Income Transfer Efficiency of Farm Support Measures”, AGR/CA/APM(2001)24/FINAL, OECD Publishing, Paris.

World Bank (2013). Ukraine: Agricultural Policy Review. Report No 83763, 2013

Nivievskyi, O. (2016). ‘Impact of the Agricultural Tax Exemptions on the Sector Productivity’ article at VoxUkraine

World Bank (2016). VAT and Agriculture in Kazakhstan. Joint Economic Research Program.

Nivievskyi, O., D. Nizalov and S. Kubakh. On consequences of introducing a minimum duration of rental contracts for agricultural lan. Analytical paper, Project «Capacity Development for Evidence-Based Land & Agricultural Policy Making in Ukraine» at Kyiv School of Economics; www.land.kse.org.ua

Demyanenko, S. and V. Galushko (2004). Shifting Agricultural Policy Towards Measures Envisaged by the Green Box. In S. von Cramon-Taubadel, S. Demyanenko, and A. Kuhn (eds). Ukrainian Agriculture. Crisis and Recovery. Shaker Verlag.Aechen.